The shepherds of the Zugspitz Arena Bayern-Tirol: When the hat is read out

One thing is simply part of hiking in the mountains: the ringing of cowbells. But how do the animals actually get to the mountain pasture? And how does the shepherd in the Zugspitz Arena Bavaria-Tyrol get his "little sheep"? Joseph Grasegger, board member of the Partenkirchen pasture cooperative, explains the traditional "Hutverlas".

For hikers it is the ultimate: you sit with your coffee, enjoy the panorama, but also the cheerful ringing of cow and sheep bells. What would an alpine pasture be without animals? The fact that cows and sheep have always been able to graze peacefully at altitude is thanks to the shepherds. And because a good herdsman is worth his weight in gold, the people in charge of the pasture cooperatives in Garmisch and in Partenkirchen take a lot of time during the so-called "Hutverlas". This is the name of the traditional procedure in which suitable herders are selected every year in the Zugspitz Arena Bavaria-Tyrol for the grazing season from 1 May to 31 October. The term comes from the "hat", the herding of the animals and the "Verlesen", i.e. the selection.

24-hour days and lots of exercise

"Every first Sunday after Shrove Tuesday, we look for shepherds for our pastures at the 'Hutverlas'," explains Joseph Grasegger, board member of the Partenkirchen pasture cooperative. The applicants sit in their traditional costumes in the inn and are then called into the next room. According to Grasegger, what counts most is experience. "It is particularly important to us that the applicant has an agricultural education." Then the salary, the annual routine and the tasks are discussed. A herdsman in the Zugspitz Arena Bavaria-Tyrol must also be fit for sports. "It's a tough job, you lose quite a few kilos," says Grasegger. Especially the shepherd has "a 24-hour day, he has to walk a lot." Since the animals have their habits and gather in the same groups every summer, it is much easier for a shepherd to remember their preferences.

Shepherd in the Zugspitz Arena Bayern-Tirol - no easy task

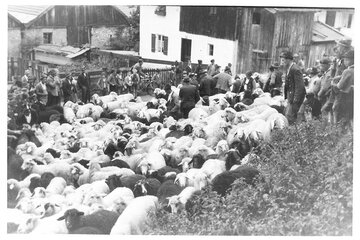

A shepherd in the Zugspitz Arena Bavaria-Tyrol has to remember a lot, because the flocks are large. In Reintal, according to Joseph Grasegger, there are about 630 sheep that move from pasture to pasture up to the Schachen. And there are also enough cattle: on the Wetterstein, for example, one shepherd is responsible for about 120 young animals and has to look after each one once a day. He is supported by the chief of the herdsmen, the Almmeister, who looks after the alpine pastures, for example.

"A shepherd has to love the animals, he has to recognise if one is sick, be able to catch it and fetch the vet," Grasegger explains. Good leadership is also needed for the change to the next pasture and for driving the animals up and down the mountain pastures. And so that the time on the mountain pasture doesn't get lonely, many shepherds take the whole family with them up the mountain. The family then usually takes care of the management and the visitors. So at the end of the day, everyone gets their money's worth.